Frederick Douglass’s Celtic Connections: Guest blog by Alasdair Pettinger

On our Trad Trail Tour for Celtic Connections we mention Frederick Douglass, a fugitive from American slavery who became a leader of the abolitionist movement, and the time he spent in Glasgow. We’re delighted that Alasdair Pettinger, Information Manager at the Scottish Music Centre has written about Frederick Douglass’s Celtic Connections for us. Alasdair’s new book about Frederick Douglass’s visit to Scotland, Frederick Douglass and Scotland, 1846 is available from Edinburgh University Press , to order from all good bookshops, or request a copy from your library.

Alasdair posts about Frederick Douglass here @fd_scotland

When Frederick Douglass arrived in Glasgow in January 1846, he was just 148 years too early for Celtic Connections. But like many musicians performing at the festival today he drew large and enthusiastic audiences to the City Hall for his first public appearance in Scotland. Notices promised a ‘lecture on American slavery’. What they got was a gripping account of his own escape from bondage in Maryland and passionate denunciations of the system that continued to prevail in the United States where even fugitives in the so-called ‘free’ North lived with the daily threat of recapture.

That threat was one reason why Douglass had crossed the Atlantic the previous summer. But he didn’t come to hide. Though still in his twenties, he was already an experienced anti-slavery campaigner. He had spent the previous four months touring Ireland, impressing those who flocked to hear his eloquent speeches. Sometimes he would even break into song. At a temperance meeting in Cork, he was welcomed by a local singer with his own composition, ‘Céad Míle Fáilte’, sung to the tune of ‘Old Dan Tucker’. According to a newspaper report, Douglass ‘was so moved that he sang unsolicited with great effect, and power, a noble Abolition song’ to the same melody. This was probably ‘Get Off the Track’ by the Hutchinson Family, who had accompanied Douglass on his voyage from Massachusetts.

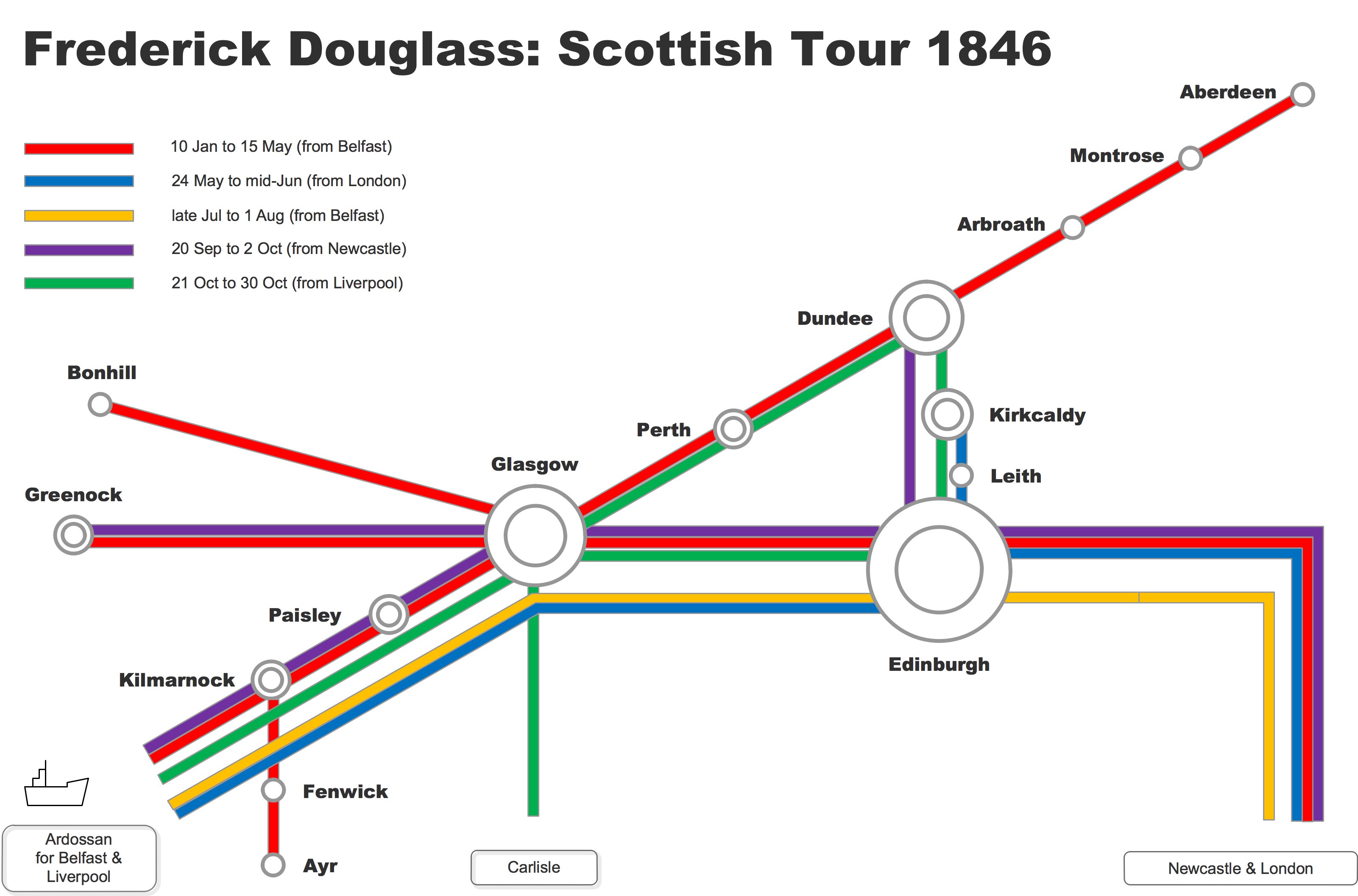

He would address over seventy meetings in Scotland, though there is no record of him singing at any of them. He may have had second thoughts when he found that his vocal talents were sometimes greeted with the kind of amusement normally reserved for blackface minstrel entertainers who were all the rage at the time. In Limerick Douglass had sharp words for ‘one of these apes of the negro’, as he put it, referring to a certain W. H. Bateman whose performances were advertised alongside his own. In Glasgow he must have felt just as uneasy competing for audiences with Dick Pelham and his American Sable Brothers who enjoyed a long run at the Monteith Rooms on Buchanan Street, offering what they claimed to be ‘unrivalled delineations of Negro Life and Character.’

More to his liking would have been the songs inspired by his campaign to persuade the Free Church of Scotland to break its ties with the American churches, which abolitionists had long condemned as the ‘bulwarks of slavery’. Having accepted donations from Southern Presbyterians, the Free Church faced calls that they ‘Send Back the Money’. The slogan, Douglass was pleased to report, was chanted at meetings, daubed on walls, and quoted in reworkings of traditional ballads.

Douglass was well-acquainted with the tradition. An edition of Robert Burns was the first book he purchased after his escape from slavery, and he made time to visit the poet’s sister Isabella when he was in Ayr. Viewing a marble bust of Burns, he wrote in a letter: ‘I received a vivid impression and shared with him the deep melancholy portrayed in the following lines’ – going on to transcribe the two verses of ‘The Banks o’ Doon.’

An ocean apart from his wife Anna and their four young children for what turned out to be nearly two years, Douglass certainly had his moments of low spirits. In such a mood in Edinburgh one day he saw an old violin for sale in a music shop. ‘The thought struck me – it has been so long since I played any that it might do me some good,’ he confided to a friend. He bought the instrument and took it up to his hotel where he played ‘The Campbells are Comin’. ‘I had not played ten minutes before I began to feel better and – gradually I came to myself again and was lively as a cricket and as loving as a lamb. It is a terrible feeling and I advise everybody to keep clear of it who can – and those who can’t to buy a fiddle.’

Alasdair Pettinger