Harlem 69: Stuart Cosgrove Guest Blog

Ahead of the launch for Stuart Cosgrove’s Harlem 69, the final part of his epic soul trilogy at The Admiral Bar this Saturday (20th October), Stuart writes about Curtis Ousley, aka King Curtis, one of the most prodigious musicians in America, at the height of his considerable powers in 1969.

King Curtis and the Ghetto Odyssey

Curtis Ousley sat motionless in a darkened bar cradling a whisky-sour. He was alone, determined not to be noticed. A brown bucket-hat sat next to him and tucked inside the bowl of the hat, hidden from view, was a pair of round prescription glasses. When he wore the hat jauntily on his head, Ousley had the street-smart look of a Harlem gangster, but the glasses seemed to put years on him, rounding his face and giving him the demeanour of a Theology Professor, who had taken the wrong turning at Columbia University. Curtis Ousley was immersed in music but he was never soul’s most fashionable star and although the New Year was only a few days old he had much on his mind, a crowded diary of engagements, the perpetual task of amassing the best band in Harlem, and most distressingly of all, a marriage that had reached breaking point. He hid everything behind a taciturn smile, nodding periodically at the barman, averting his eyes up to the bruised-purple lamp shades that hung singeing above the gantry, nodding at the line of liquor bottles as if they knew how he really felt. Oddly, for a man so immersed in music, he never glanced through the fog of smoke to the jazz quartet on the dimly-lit raised stage. He was there to listen and not to watch. Periodically, Ousley would tap out percussion on the walnut wood with the edge of a beer-mat, keeping time with the drummer, rarely letting the syncopation falter, and then suddenly with a flash of his plump fleshy right hand he would work brief routines up and down his dimpled glass, his fingers motioning the notation of a tenor saxophone. Ousley was drained of any obvious emotions – neither pleasure nor discontent – his mind wandering off into the slipstream of music. Each night, when his own show was over, he delayed returning home and would disappear for hours, scouting the bars and nightclubs of Harlem in search of the next flicker of talent. King Curtis was the most gifted musician in Harlem, he was at the height of his considerable powers and although he still had the energy to form another great band, inside he felt bereft, deadened by the shouting and screaming, unwilling to face up to his own shortcomings, and staring divorce sullenly in the face. In the months to come as his relationship with his wife would sour into irresolvable acrimony. His wife Etheleyn, a dancer he had met on tour in the Bahamas, had already served him with divorce papers sighting his absence from home, adultery and cruelty. It was a divorce he never fully contested.

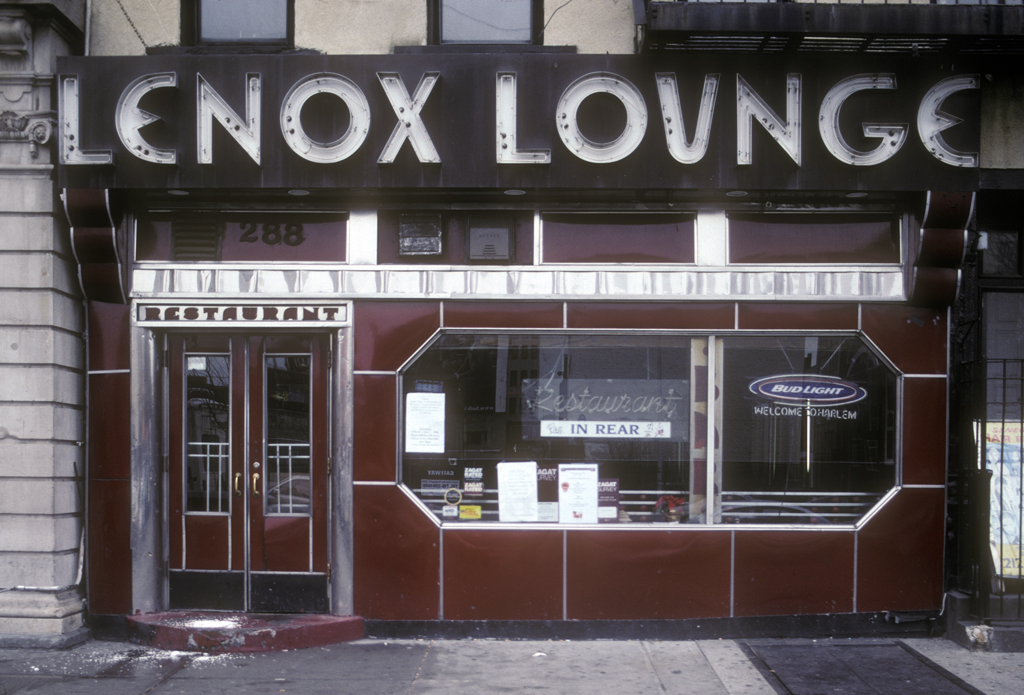

The late Lenox Lounge in Harlem, legendary venue that hosted jazz greats Billie Holiday, Miles Davis & John Coltrane, now demolished.

By 1969, King Curtis was staring at a seemingly relentless schedule of activity. He was contracted to provide musical-director services to Atlantic Records, he had signed up to tour with Aretha Franklin, he had an obligation to fulfil a residency at Club Baron on the Corner of 132nd Street, sharing the residency with George Benson, and had recently agreed in principle to take on a new role as a musical producer and bandleader at a fledgling television show called ‘Soul’ on Channel 13. Curtis had recently returned from a European tour with the Sweet Inspirations and soul singer Deon Jackson and was fighting a losing battle with time. To try to buy himself more hours in the day, he had once bought Cannonball Adderley’s customised railway carriage hoping to save wasted time at airports by travelling to distant venues hitched to a Pennsylvania Railroad train. But the train was ageing and needed constant repairs and the time he saved on journeys was eaten up with endless phone calls to railway engineers.

Although he spent at least half the year on the road, King Curtis knew Harlem better than an old friend. He could map it out in his mind – the corner shops, the liquor stores and the laundromats – and he could check them off like an octave as they hugged the road north on Lenox and across 110th Street. He was a born survivor who through a mixture of talent and dogged professionalism, had surfed the many changes that music had thrown at him. Still in his mid-thirties, he was one of a minority of musicians who had successfully clung to the rollercoaster of black music as it rattled recklessly from big band, to be-bop, to doo-wop, to rhythm and blues and triumphantly into sixties soul. Something deep inside him – an instinct – told him it was all about to change again, this time the change would be meteoric and he couldn’t be sure he had the strength left to survive. Each night, to escape from home and to find time to think, he had taken to walking the streets of Harlem at night, watching, listening and second-guessing the rhythms. He braced himself for a time when soul music would fragment into jazz-funk, psychedelic soul, underground disco and the mighty messages of a more political ghetto.

King Curtis’s midnight odyssey – searching the nightclubs for the next great instrumentalist – took him on a journey of composed decadence. He could recite the bars on 125th Street as if they were his old school classmates – the Hi-Hat, the Baby Grand and Palms Cafe, there was Mr. B’s, Willie Abraham’s Gold Lounge, and the Shalimar. Ousley had a good memory for faces and knew the Rabelaisian characters who populated those late night streets: the label-owner and bon viveur Fat Jack Taylor; the “polyunsaturated pimp” Fast Eddie; the exuberant and super talented Allen Twins; the wayward basketball star Earl ‘The Goat’ Manigault, the bootlegger and record-store owner Paul Winley; the effervescent radio DJ Frankie ‘Loveman’ Crocker, and the statuesque Mademoiselle Mabry, an ultra-glamorous fashion model who had married jazz legend Miles Davis. King Curtis always gave people time but in a way that avoided any lasting conversation, he was fixated with tracking down the best of the next generation – saxophonist Lonnie Youngblood, master-drummer Bernard Purdie and the virtuoso keyboard player Herbie Hancock – they were either sitting-in with Harlem bands or hanging out at Smalls. Curtis usually had session-work to hand out but his motives were not always altruistic, he liked to pick up fragments of gossip, who was coming to town who was forming a band, who was recording, but most of all what was the next turn of the wheel. As he walked home to his apartment, sometimes so late that the sun was already rising, King Curtis hummed the jazz standard ‘Harlem Nocturne.’ He had played that tune so often it had become a poetic soundtrack to his late night sojourns, a piece of music, suffused with nostalgia that conjured romance, creativity and black achievement. But King Curtis sensed that the era of the nocturne and its magic was under threat, engulfed by Harlem’s darker personality, the crime, the poverty and the consumptive epidemic of heroin abuse.