Small Hours:The Long Night of John Martyn by Graeme Thomson — Glasgow Walking Tours Blog

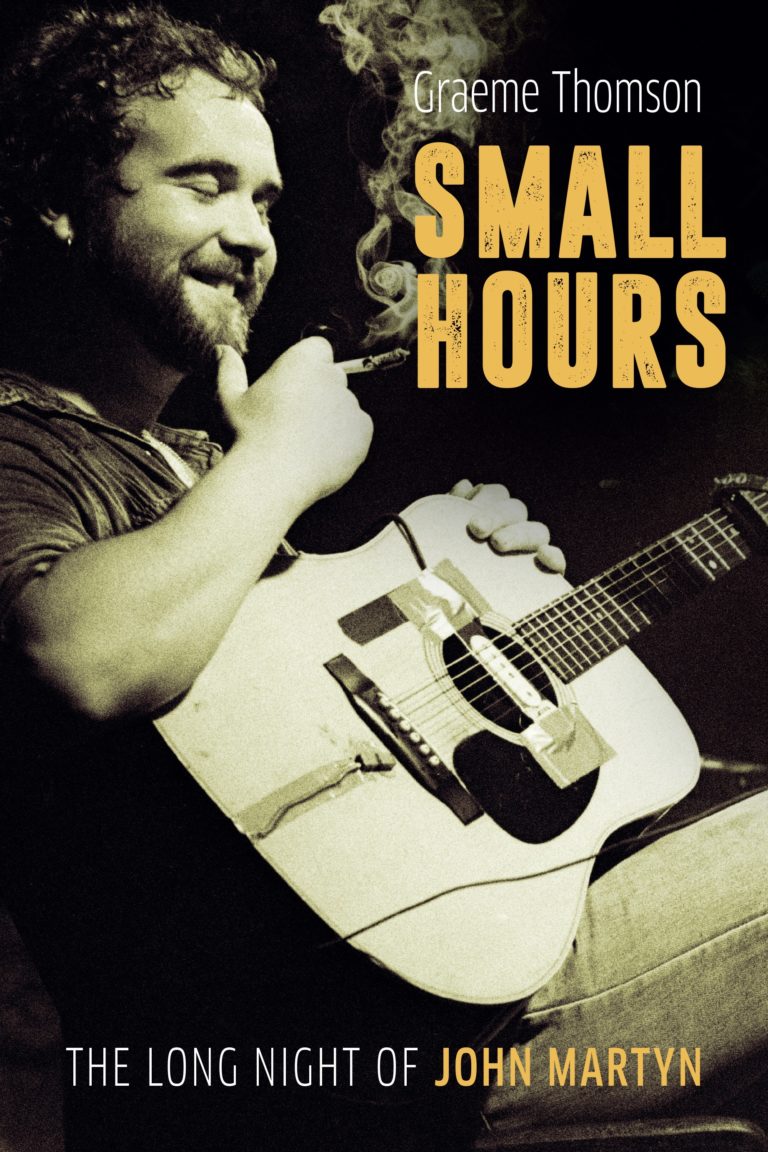

Graeme Thomson’s excellent new book, Small Hours: The Long Night Of John Martyn, was published earlier this month and has been praised by the Observer, Irish Times, Independent, the Herald, Uncut and MOJO. Omnibus Press have very kindly given us two copies to give away, check our FB page for details on how to win a copy.

We’re delighted that Graeme has allowed us to share this extract, in which he writes about Martyn starting out in the folk clubs of Glasgow in 1966 and 1967, and his formative relationship with his lifelong friend and mentor, Hamish Imlach. Over to Graeme…

John Martyn made one of his earliest appearances at Clive’s Incredible Folk Club. A memorable if short-lived venture set up by the Incredible String Band’s Clive Palmer, it ran for ten weekends in the spring and early summer of 1966. Martyn was 17, and still performing under his birth name, Ian McGeachy. ‘We booked everyone we could,’ says Palmer’s fellow String Band member, Mike Heron. ‘[John was] one of the young guys that we thought was outstanding, so we got him to do a set. He was really just into the music back then. He wasn’t really wild.’

Clive’s was housed in the fourth floor of a disused office block at 134 Sauchiehall Street. The whole room, including the windows, was painted matte black. Access was via an ancient cage-like lift ‘or way up a rickety set of stairs,’ recalls Rab Noakes, one of the legions of local musicians who made the pilgrimage. It ran from 10 p.m. on Saturday until 5 a.m. on Sunday and everyone came and played, including the String Band, Davy Graham, Bert Jansch, Billy Connolly, Wizz Jones, Alex Campbell, Matt McGinn and Les Brown, whom Martyn claimed gave him his first taste of hashish around this time.

Charismatic entertainer

Hamish Imlach was the resident master of ceremonies. Eight years older than Martyn, Imlach was a broad oak in Scotland’s traditional music landscape. A popular folk singer-songwriter, he was a consummate blues guitarist and charismatic entertainer, as adept at penning anti-nuclear protest songs as he was at writing wry social comment or winking comic doggerel. He honed a highly successful career in Scotland and further afield with his mixture of traditional material, American blues, risqué parodies and shaggy-dog stories. He recorded for Transatlantic Records, sang in pubs and at peace demos, and became a critical link between old and new folk currents.

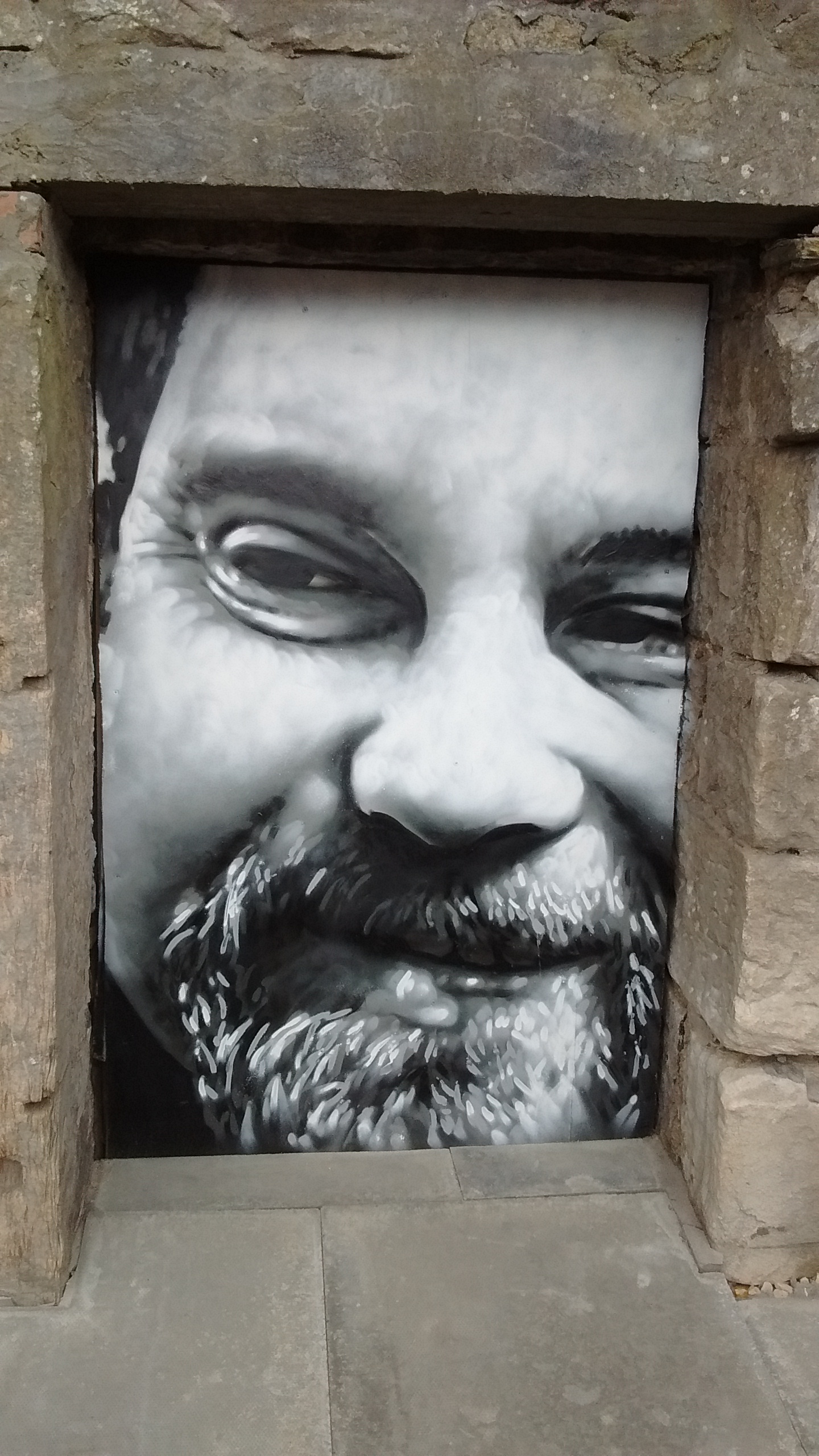

Hamish Imlach on the Clutha pub mural in Glasgow

In Imlach’s biography, which he co-wrote, the musician and author Ewan McVicar summed up the range of his gifts succinctly as ‘a raconteur who taught Billy Connolly, a singer who taught Christy Moore, a blues guitarist who taught John Martyn’. He was a large man, and larger than life. Says McVicar, ‘I only met one person who had a bad word to say about Hamish, and that was a girl whose flute he’d sat on and bent.’

Imlach gladly welcomed all manner of waifs and strays into his home. He lived on the top floor of a three-storey council block at 152 Muirhouse Road in Motherwell with his wife Wilma and their four children, who were turfed out of their beds whenever a visitor needed it, which was often. Martyn joined his ragged coterie – Christy Moore remembers first meeting Martyn at Muirhouse Road – and in time became part of the family. Wilma Imlach, who died in 2019, would always talk about his ‘wee angelic face’. Imlach became Martyn’s new school, where he learned the rudiments of a bluesy acoustic guitar style.

As well as appearing at Clive’s, Martyn became a fixture at the Glasgow Folk Centre. In 1960 Ewan McVicar and Drew Moyes had opened the Glasgow Folk Song Club. A Sunday-night gathering in a lunch club called the Corner House, situated opposite the Tron Theatre on the Gallowgate, it was a spartan affair. ‘We used to have to stop singing when the tram came by, as it was too loud,’ McVicar recalls. In time the club was blessed with a rudimentary PA, slung on the top of a pole.

After a couple of years, Moyes opened the Folk Centre in a disused industrial space on Montrose Street, behind the City Chambers. It had previously housed sewing machines and consisted of a large open room with a smaller room at the rear, and a stage with a battered piano on it. It became a hub for all manner of emerging local artists, alongside well-known national and international acts. A music programme ran every night of the week. During the day, there were workshops and instrumental lessons, even a record-lending club.

A wee bit of a swagger

Appearing regularly at the Folk Centre, Martyn began to register on the radar among his peers. ‘He was a good-looking young man, confident, with a really good voice,’ says Rab Noakes, who made his debut during the same period. ‘He had a wee bit of a swagger about him that was rare in one so young. It wasn’t anything obnoxious; he was just quite cool and aware of his own capabilities.’ The influence of American blues was strong in the clubs at the time. This suited Martyn, whose guitar style, shaped by Imlach, betrayed his love of artists like Mississippi John Hurt. ‘It was mostly a bluesy repertoire,’ says Noakes. ‘He had a really interesting finger style. If there was any Hamish Imlach influence, it would be in his guitar playing, and the subtle art of stagecraft. From an early age he knew how to hold people’s attention.’

Even back then, Martyn was the kind of presence who tended to fill a room. Not all rooms desire to be filled; some prefer a little elbow room. His boisterous self-belief could occasionally grate. ‘We’d go to folk clubs together and have fun,’ says Linda Thompson. ‘He always said, “I’m going to be terribly famous, because I’m fabulous!” He was physically gorgeous and preternaturally confident. I never met anyone so sure of himself till Rufus Wainwright decades later.’

He rapidly progressed beyond Davy Graham’s ‘Anji’, the scene’s ubiquitous instrumental, to performing his own material. Billy Connolly was a member of folk trio The Humblebums, with Gerry Rafferty and Tam Harvey. A regular presence at the Glasgow Folk Centre, he recalls first hearing ‘Golden Girl’ there, a song which later appeared on Martyn’s first album. ‘I remember him singing about the green stream that meanders round his mind,’ says Connolly. ‘He was a good guy, a good laugh. He did an instrumental on the guitar using the capo; he’d slide it up and down, going up a half tone each time.’ This was ‘Seven Black Roses’, which became Martyn’s undergraduate party piece in the clubs of Glasgow and London, a flashy flourish of cheerfully contrived theatre which always went down well in the room. We’ve put a YouTube clip of John playing ‘Seven Black Roses’ below. There is a swear in the intro, just in case that sort of thing worries you.

Already, the rigidity of sections of the traditional crowd rankled. Many Scottish folk musicians were conspicuously reverent to the purity of the source material, a notion that didn’t much interest Martyn. He saw himself as liquid to their stone. ‘A lot of people didn’t like him because he queered the pitch,’ says Linda Thompson. ‘There was that thing of folkie people thinking, “Oh, he could be really good if he was more traditional.” John was very versatile, but because there was an American feel to him a lot of people disregarded him. I think he fell a little bit between pillar and post.’

https://youtu.be/c80pa9lCFjQ

***

When he played outside Glasgow, Martyn would often rendezvous with Imlach in the Montrose Bar or the Marlin before setting off in Imlach’s Mini to clubs, bars and hotels around Scotland and northern England. ‘I can remember Hamish complaining about John leaving too many sweetie papers in his car,’ says Archie Fisher. ‘He was just a nice, innocent, curly-haired young boy, who would do a spot in a folk club before Hamish.’ He was company for Imlach, rather than competition, although his attendance could cause some frustrations. Phil Shackleton recalls, decades later, Imlach still complaining about the fact that Martyn would sit in the front row and jump in with the punchlines to his jokes just before he said them. ‘Hamish threatened to kill him one night!’

It was a generous apprenticeship, a chance to hone his skills playing a 15-minute set as the opening act to an established name. As he and Imlach saw more of each other, their bond deepened. Martyn became a surrogate son, visiting Muirhouse Road for Sunday lunch, post-gig sessions, parties, family gatherings.

The flat was not merely a music hub. It was an informal seat of learning, where wit, erudition and staying power were traded as precious metals, and which provided endless social stimulation. ‘Hamish was a movable party,’ says his son, Jim Imlach. By showing rather than telling, Imlach taught Martyn how to live large. ‘If you bought one of something,’ says Phil Shackleton, ‘Hamish would buy two. John got a lot of that from him.’

At Muirhouse Road there was good food, and plenty of it: curries, spaghetti Bolognese, soups and stews simmering on the stove at all hours. It was open house, with beer, wine, spirits, music and dope on tap. Come all ye and stay awhile. Last man standing wins. ‘In the Sixties my capacity for spirits was phenomenal,’ Imlach wrote in his memoir, Cod Liver Oil and the Orange Juice, recalling how he would challenge all comers to drinking competitions. Martyn was not yet up to anything like full speed, but he observed with admiration.

John Martyn: intuitive spontaneity

When it came to the guitar, however, student quickly outstripped teacher. ‘The difference [between] John and my dad was that John had the application to practise for ten hours a day,’ says Jim Imlach. The public dazzle of Martyn’s playing was polished hard in private. Each performance was an event, with elements of intuitive spontaneity, but he always gave himself the best chance by laying down the groundwork.

He took his gifts seriously. He thought deeply about ways in which he could stand out from all the other earnest young men playing acoustic guitars. He removed the metal pin from an old elastic capo and sellotaped it over the sound hole of his acoustic guitar. He was already testing out different tunings, some of which he was shown by the String Band. Some songs were written and played in standard tuning, but he largely forswore the popular DADGAD tuning in favour of DADDAD, in which the third and fourth strings chimed in unison. Other songs were written in drop D, where the bottom E string was lowered a tone, and in open C.

Ewan McVicar recalls that early on at the Folk Centre Martyn played his songs in the same order each time, because he ‘didn’t know how he had got from one tuning to the other, in terms of the theory of it’. Instead, he simply memorised the entire routine.

In time, as is the way of these things, Martyn forgot that he had ever been a student at all. He had a lifelong aversion to any whiff of structured tuition, and would tell people, mock-indignantly, ‘Nobody taught me how to play guitar!’ – which was not entirely true, but one could see his point. He simply took what he needed and built on it. Jim Imlach studied his technique and came away baffled. ‘I watched my dad for years – he was great – but watching John up close, I couldn’t recognise one thing he was playing. There were no chords. The left arm was playing stuff that was unbelievable, and the right arm was going along with it. John’s thumb could come right over the top of the guitar and reach the second string. How do you even do that? I thought I knew how people played guitar, but he was truly unbelievable.’

Troubador’s code

Martyn may have transcended Imlach in musical terms, but much of what he learned about the texture of life as a touring musician stayed with him. From Imlach he learned by heart the troubadour’s code. ‘They had the exact same outlook,’ says Jim Imlach. ‘If you look back in history to any bluesman, you take bits from other people’s work, you pass things on to the next generation, and you drink the whole time, take drugs and have fun. That was his outlook, and that was Hamish’s outlook. John was tied up with all of that. It was the old blues tradition: you travelled, you played, you drank, you met women. I absolutely know they both felt like that. They laughed at someone like Bert Jansch, because he took the whole thing too seriously. They were a couple of wasters and they loved it.’

Imlach typified the old-school showbiz values of the Scottish west coast folk scene. ‘Edinburgh was a bit more academic; people studied folk there,’ says Mike Heron. ‘In Glasgow, they didn’t give a toss, they just wanted to have a good time. It was more boisterous.’ The city’s folk stars tended to be garrulous and versatile entertainers like Imlach, Matt McGinn, Alex Campbell and Billy Connolly. Cheek and chutzpah were highly valued. When that arch-traditionalist Ewan MacColl visited, he cocked an ear to the locals and their irreverent mix of sardonic humour, blues, skiffle, trad ballads and originals, and dismissed the whole bunch of them as tartan cowboys. Martyn, however, was practically allergic to reverence and felt at home on the range. He never forgot the value of putting on a show.

Martyn left for London in 1967, but throughout his life he returned regularly to the Glasgow clubs – and to Imlach’s flat in Motherwell. When he moved back to Scotland in the early Eighties, he stayed within striking distance of the family. It was his North Star, a kind of refuge, immune to airs and graces, where he was accepted entirely as he was. The door was always open, as was a bottle. Phil Shackleton remembers a conversation he had with Martyn many years later, in the small hours, as the snow was falling outside his cottage in Roberton in South Lanarkshire. ‘He said to me, “It was always great to stop at Hamish’s. You’d get up in the middle of the night and peep in the bedroom, and Wilma was laid in bed there with all the kids cuddled up around her. It was beautiful.” That was Ian McGeachy talking. He was soft as hell, really.’

Falstaffian, Rabelaisian, wildly immoderate and endlessly generous, Imlach died, hugely overweight and somewhat diminished, on the first day of 1996, at the age of fifty-six. The parallels with Martyn are striking. Perhaps the pupil learned too well.

Graeme Thomson

Small Hours: The Long Night of John Martyn is available now from all good bookshops and Omnibus Press. Thanks to Graeme for sharing this with us.