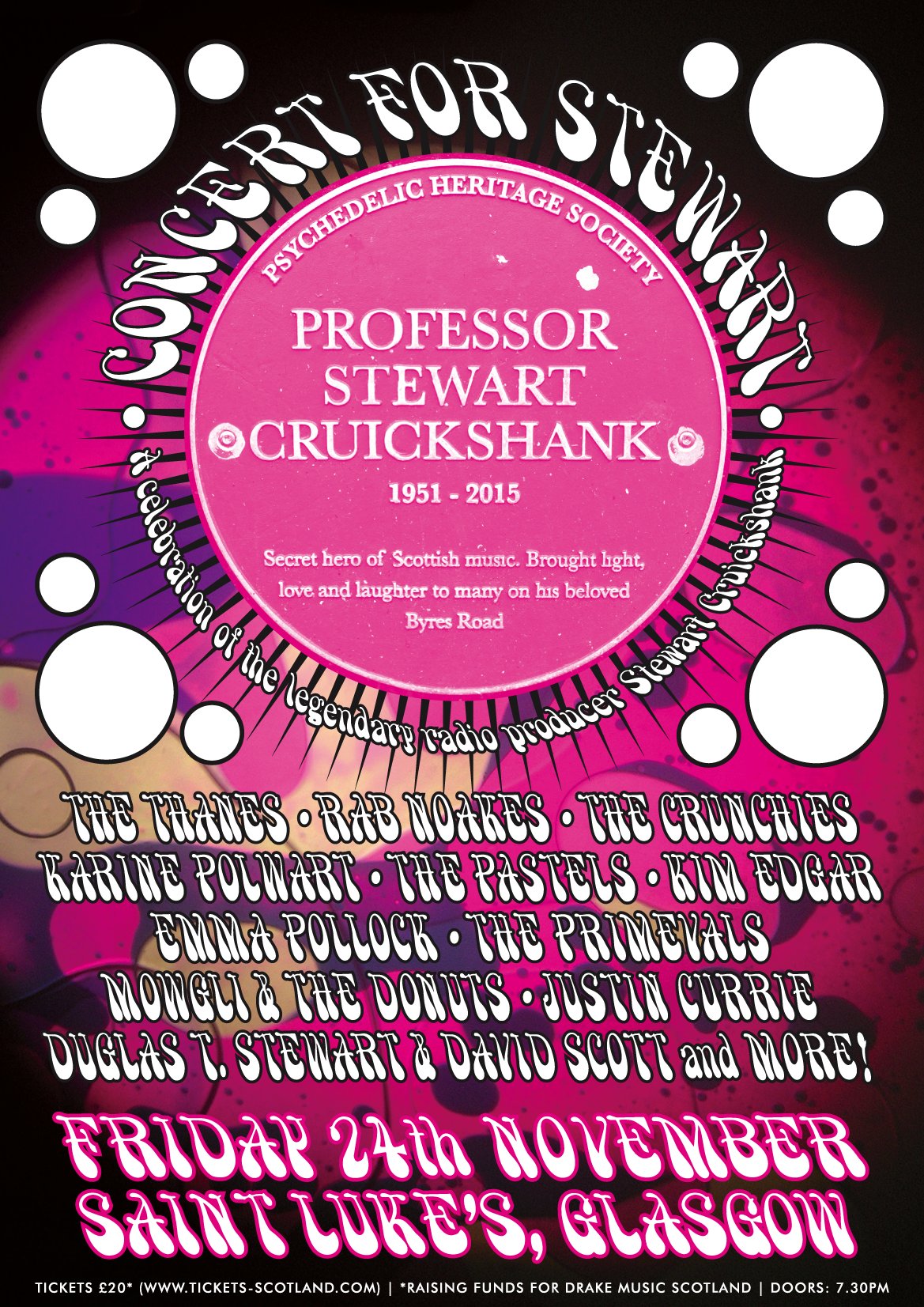

Concert for Stewart: Guest blog by Rab Noakes

On Friday November 24th Saint Luke’s will host a celebration of the legendary radio producer Stewart Cruickshank, who lived for music and for people. His work from Beat Patrol to the Iain Anderson show gave a start to countless musicians and enriched the lives of all music lovers in Scotland. He made things happen, brought people together, and always shared his knowledge and his wisdom unstintingly. One of the musicians appearing is Rab Noakes, who has written this lovely guest blog on his memories of working with Stewart. Big thanks to Rab for taking the time to do this.

The concert is raising funds for Drake Music Scotland and tickets are available here We look forward to seeing you there! Over to Rab…

I knew Stewart a little in the early 1970s but got to know him better at the BBC in the 1980s. At that time he was working in the Gramophone Library and I was doing work on Radio Scotland shows, mostly the afternoon show presented by Art Sutter. Over and above his librarian duties Stewart, along with his colleague, Sandy Semeonoff, and presentation announcer, Peter Easton, produced a vital new-music show called Rock on Scotland, which went out late on Friday nights. Stewart had also produced a definitive story of rock’n’pop in Scotland called Beatstalking.

This was all around the beginning of my time at the BBC and I eventually applied for, and got, proper jobs. The first one was in Popular Music, part of the Network Radio Department in Manchester. Whilst I was there I was offered an attachment at Radio Scotland as Senior Producer in the Entertainment Department. This was late 1988 and one of my initial notions was that I wanted to get Stewart into the Department. There was no obvious vacancy so an inventive strategy had to be applied. By coincidence, he was on attachment in Manchester at the time with the TV show No Limits. We met one day and I suggested a good idea could be The Simple Minds Story for Radio 1. I had good relationships with the networks and as The Minds were riding high at the time with the Street Fighting Years album imminent, there was a good chance they’d take it. We did get the commission, not long after I started at Radio Scotland so we were off. It was good for me too, in terms of kudos, getting a high-profile Radio 1 commission, produced in BBC Scotland. Anyway, it got Stewart into the department as intended and, following some reorganisation, a wee while later I was appointed as Department Head. Stewart applied successfully for the Senior Producer position and there commenced a long and fruitful working relationship.

I like to think we revitalised the popular music programming to its advantage. We also created a lot of interesting opportunities for younger staff members, especially women. Making something like that work in an organisation like the BBC, not to mention dealing with the internal competition for airspace in Radio Scotland, can be quite complex. There’re a lot of politics to deal with along with a lot of decisions from above. I dealt with most of that while Stewart kept everything upbeat with the staff. I had to be the bearer of less palatable decisions sometimes but I like to think it worked well. Stewart, although somewhat creatively dishevelled in his methods at times, was always hard-working, dedicated and productive. He produced hundreds of hours for Radio Scotland and made a mark with some exclusive network commissions with the likes of Lou Reed and Jim Webb. We became and remained really good friends and were in touch a lot after I left there in 1995 to form Neon Productions with my wife, Stephy Pordage.

One anecdote I recall, to the best of my recollections, was one Stewart told me of a typically serendipitous event. Stewart and his fellow band members (Mowgli and the Donuts) were out and about in the streets of Central Edinburgh one day in the early ’70s when they bumped into Viv Stanshall. They weren’t surprised, as they knew he was there to play in town that evening. They were excited though and talked to him, probably in some detail, about the Bonzos and other exploits. Stanshall was slightly bewildered but delighted by all the attention. He invited them to the show to which they replied, “We’re coming anyway”. “You’re coming and you’re a band well, there’s a thing dear boys. Why don’t you be my backing band for tonight”. This they did and, according to Stewart, it went fine. They knew the songs well enough and fitted the looseness of a Stanshall performance ideally.

The other anecdote was one I saw first-hand and was part of. It was 1992 and Stewart and I were representing Radio Scotland at the Radio Academy Festival in Birmingham. I was a bit of a regular at this event by then but this was SC’s first visit. After we’d arrived, the day prior to its commencement, and checked ourselves into the adjacent Hyatt we made our way to the Conference Centre where things were in a pre-event stage. We walked into the Exhibition Room and the first person we saw was Elliot Mazer. Elliot produced a couple of albums of mine in the ’70s and was now working for a broadcast tech company RCS. They pioneered intro-recognition software and the early Selector systems. Elliot and I greeted one another as the long-lost pals we were and I introduced Stewart. Stewart immediately posed Elliot a question about a band he’d produced in the ’60s for the Cameo-Parkway record label. Elliot was a little taken aback by the question but enjoyed encountering such in-depth knowledge. I was impressed, as I so often was, with Stewart’s ability to release the most surprising, yet erudite, information on the intricacies of pop’s rich story at the drop of a hat.

Working within the BBC you have to be quite wily to make things like that happen. I loved working with Stewart. It wasn’t quite good cop bad cop. I was the one who had to deliver the bad news sometimes when strange decisions came from above but Stewart always had the full support of everybody because they loved him. Everybody who came into contact with him loved him because he was such a lovely person.

![]()

Stewart in his element on stage at the Panopticon on our tour

He was deeply interested in the whole space programme –there was a wee spiritual edge to Stewart. He was a very interesting man, you could spend a lot of time just talking with him; he was bright and knowledgeable on a number of subjects. His detailed knowledge of pop music was exemplary, but it was also symptomatic of the approach Stewart had to things. He did like attention to detail and that made him good as a producer but it made him a really interesting companion. I miss him. We had a lot of phone calls into the night.

At the concert I’ll play songs that have a direct connection with Stewart. I’ll also perform a couple in collaboration, I’ll enjoy doing them, it adds a collectivity to the proceedings, Stewart was great at bringing folks together, he was a true producer in that sense. It’s a dying art in broadcast production now, the kind of things that Stewart was good at are not a currency that is much in demand nowadays – producing people, putting them together, coming up with ideas. Far too much of current radio production is based on off-the-peg stuff and I think Stewart did adhere to the BBC being a genuine patron of the arts and he worked hard to comply with that and make a contribution to that principle.