Guest Blog: Graeme Thomson on Themes For Great Cities, A New History of Simple Minds

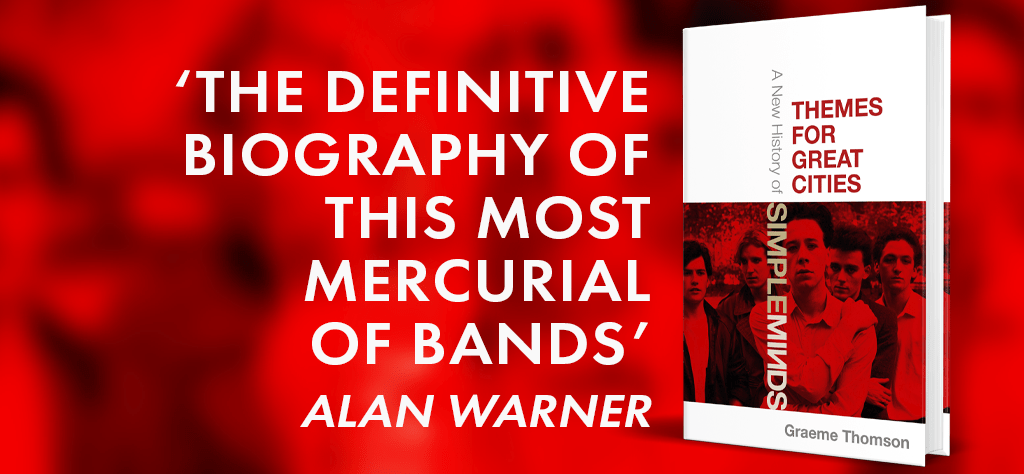

To celebrate the forthcoming publication of Themes For Great Cities: A New History of Simple Minds by Graeme Thomson (published by Constable on 27 January) we’re delighted that the author has penned a brilliant guest blog for us. We also have a one copy for one lucky winner in a giveaway, lookout for details coming soon over on our Facebook page. Praised by Alan Warner and Ian Rankin and already garnering rave reviews, Themes For Great Cities features extensive new interviews with Jim Kerr, Charlie Burchill, Mick MacNeil and Derek Forbes. It has a particular focus on the period 1978-1985, shedding new light on the band’s dazzling and eclectic art-rock legacy.

Graeme has chosen six Simple Minds songs with a particularly resonant connection with Glasgow, the band’s home city. Each clip is accompanied by a themed extract from the book.

Pleasantly Disturbed (1978/79)

‘Pleasantly Disturbed’ was written shortly before the first Simple Minds show – at Satellite City in Glasgow on January 17, 1978. Simple Minds were third on a four-band bill headlined by British reggae group Steel Pulse, who borrowed Brian McGee’s drum kit for their performance. The rest of the talent was local. Second on the bill were The Backstabbers, aka Rev Volting & The Backstabbers. Simple Minds went on after opening act Nu-Sonics, who changed their name to Orange Juice a few weeks later.

Symbolic of the dawning of a new band and a new sensibility, with ‘Pleasantly Disturbed’ Kerr and Burchill felt they were getting somewhere with their writing. ‘We’re about to rehearse it today,’ says Kerr, forty-two years and four weeks later. ‘I think that was the second song Simple Minds ever wrote. It’s a real opus.’ While derivative of their influences, the song showed ambition and a gift for building atmosphere. It was the first halfway persuasive reply to the question Kerr and Charlie Burchill were already asking themselves: ‘How do you write good songs?’

Running to eight minutes, ‘Pleasantly Disturbed’ was clearly influenced by the dragging, opiated tempo of The Velvet Underground’s ‘Heroin’ and ‘Venus in Furs’, deadened drums, droning violin and all. The Doctors of Madness are in there. The corkscrewing guitar riff sets the tone for Kerr’s disquieting words, which scratch at the underbelly of the city – loneliness, drugs, darkness, violence, paranoia. It is a requiem for those in the unloved corners of the metropolis whose reasons for their actions are ‘not all [their] own’: ‘I’ve seen the streetlights shine on the underground / I’ve heard the dead fight when there’s no other sound.’ Nobody here is safe, nothing is certain. Somehow you sense the singer wouldn’t want it any other way.

Pleasantly Disturbed (demo):

Theme For Great Cities (1981)

‘Theme for Great Cities’ is a dizzying thing, Delia Derbyshire on chemical overload, powered by swirling sci-fi atmospherics and astounding rhythmic thrust. Take some time to focus solely on the drum track. Hear how it drives the whole enterprise, yet still Brian McGee finds the space and time to surf through with a series of almost jazz-funk fills. Not even the revelation that the track’s working title was ‘Do You Want Anything from the Van?’ can diminish its mystery and power.

‘“Theme For Great Cities” was Charlie and I, really,’ says Mick MacNeil. ‘I was living with my mum at the time, and I always remember sitting in her spare room, downstairs in Priesthill, in this tiny council house, and there was something about the tune that reminded me of the ice-cream van. Charlie and I would say, “Do you want anything from the van?” When we took it to Derek and Brian, we got the beat, and it just fell together. The bass is amazing.’ Prior to pre-production at Monnow Valley in Wales, MacNeil had handed a Portastudio cassette of the instrumental track to Kerr. It knocked the singer out. ‘It was pretty much as it is,’ says Kerr. ‘I remember walking around Toryglen Circus at night, over at the railway behind Charlie’s block. It was fucking phenomenal. Beautiful. I didn’t know it was going to be instrumental. I thought, I’ve got to find words for this, and I will find words, but anytime I did it felt clumsy.’

The American (1981)

Kerr recalls writing the lyrics to ‘The American’ at the kitchen table of his childhood home: on the eleventh floor of the tower block at 24 Crossbank Road in Prospecthill Circus, Toryglen. It’s oddly touching to think that these modernist songs of adventure were often written in the most prosaic surroundings. ‘I still lived with my mum and dad,’ says Kerr. ‘I never had a girlfriend at the time, and it didn’t make sense to rent a flat because I was never there. [The band] lived in Glasgow and at the same time we lived everywhere, because we were always on tour. Even up until after New Gold Dream, that was still the case.’ When Simple Minds were recording in London, after the session ended Kerr would often catch the late shuttle back to Glasgow and then take a taxi to Toryglen. En route, he would stop off at Radio Clyde in the city centre, ask the cab to wait, and deliver an acetate of the latest Simple Minds song for the attention of Billy Sloan. ‘I’d come in to find a scrawled note from Jim,’ says Sloan. ‘“This is ‘The American’, it’s the first copy. If you like it, play it.”’

Love Song (1981)

When sound engineer and ‘invisible member’ David Henderson stopped working with Simple Minds in 1980, he opened the Hellfire Club in Carnarvon Street, a rehearsal and recording studio partly stocked with old equipment donated by the band. Kerr, meanwhile, had a plan for David’s sister Jaine, also an ‘invisible member’ and Simple Minds’ original lighting engineer. ‘Jim said he would write a song for me to sing and record,’ says Jaine. ‘Jim and Charlie came to the Hellfire Club one night and Jim recorded the guide vocal to it. I’m not a singer, never wanted to be a singer, but I sang it and never let anybody hear it. A few months later Jim asked if he could record it himself! I said OK. That was “Love Song”.’

David Henderson recalls the Hellfire version of ‘Love Song’ being ‘quite experimental. I remember Jim and Charlie coming in with a wee Portastudio. It has a drum machine going through an FX pedal.’ The song had been born a short time beforehand, during rehearsals in Edinburgh. ‘It started with that noise I made up on the old Jupiter-4,’ says MacNeil. ‘Jim got all excited and the bass came quickly after. Magic moment.’ Even on the demo, ‘Love Song’ moves through the air with blood-rushing compulsion. It is rougher, rowdier, more abrasive than the final version, propelled by a deep bass rumble. The lyrics are already in place, as are Burchill’s Morse code bursts of guitar and the upward rush of the chorus. Though the version with Jaine Henderson never saw the light of day, the band clearly envisioned a woman’s voice on the song. The band demo recorded at CaVa studios in Kelvinside features both an extended drum breakdown and a breathless female vocal.

Love Song (CaVa demo):

Waterfront (1983)

‘There was something about the melody Derek played that made me think of a Celtic or Gaelic thing,’ says Jim Kerr. ‘The week earlier I had been in Glasgow, and it was one of those things where, you travel far and wide in search of something, you see things, and then you come back to your home town and you see it with fresh eyes; or a thought comes to you that hadn’t previously.’

Oh Jungleland (1985)

Once Upon a Time reached number 1 in the UK, where it was certified triple platinum and stayed on the charts for 78 weeks. In the States, it peaked at number 10 and sold half a million copies. Three songs off the album – ‘Alive and Kicking’, ‘Sanctify Yourself’ and ‘All the Things She Said’ – were significant hit singles in the UK and US, while a fourth, ‘Ghost Dancing’, reached 13 in Britain. It was a new world, and Simple Minds were in many respects an almost entirely altered proposition. For this reason, perhaps, ‘Oh Jungleland’ is my favourite song on the record. It is big but bruised; vulnerable. It is a Glasgow song, with its soul boys and love drugs, its tower blocks cloaked in twilight and its threadbare faith in hope. A song of fond but hard-headed recognition – ‘Here comes summer / Here comes violence’ – ‘Oh Jungleland’ sounded like a bittersweet farewell to a formative part of their lives. It dovetailed poignantly with a fleeting moment during Simple Minds’ set that summer at Live Aid in Philadelphia. When Burchill took a solo at the end of ‘Don’t You (Forget About Me)’ Kerr placed his hands on his shoulders, and they smiled briefly at each other. They had come a long way from Prospecthill Circus.

Oh Jungleland (Dreamland Mix):

Themes For Great Cities is published by Constable in hardback and e-book: https://www.hachette.co.uk/titles/graeme-thomson/themes-for-great-cities/9781472134004