The Sikh Pipe Band by Peter Ross

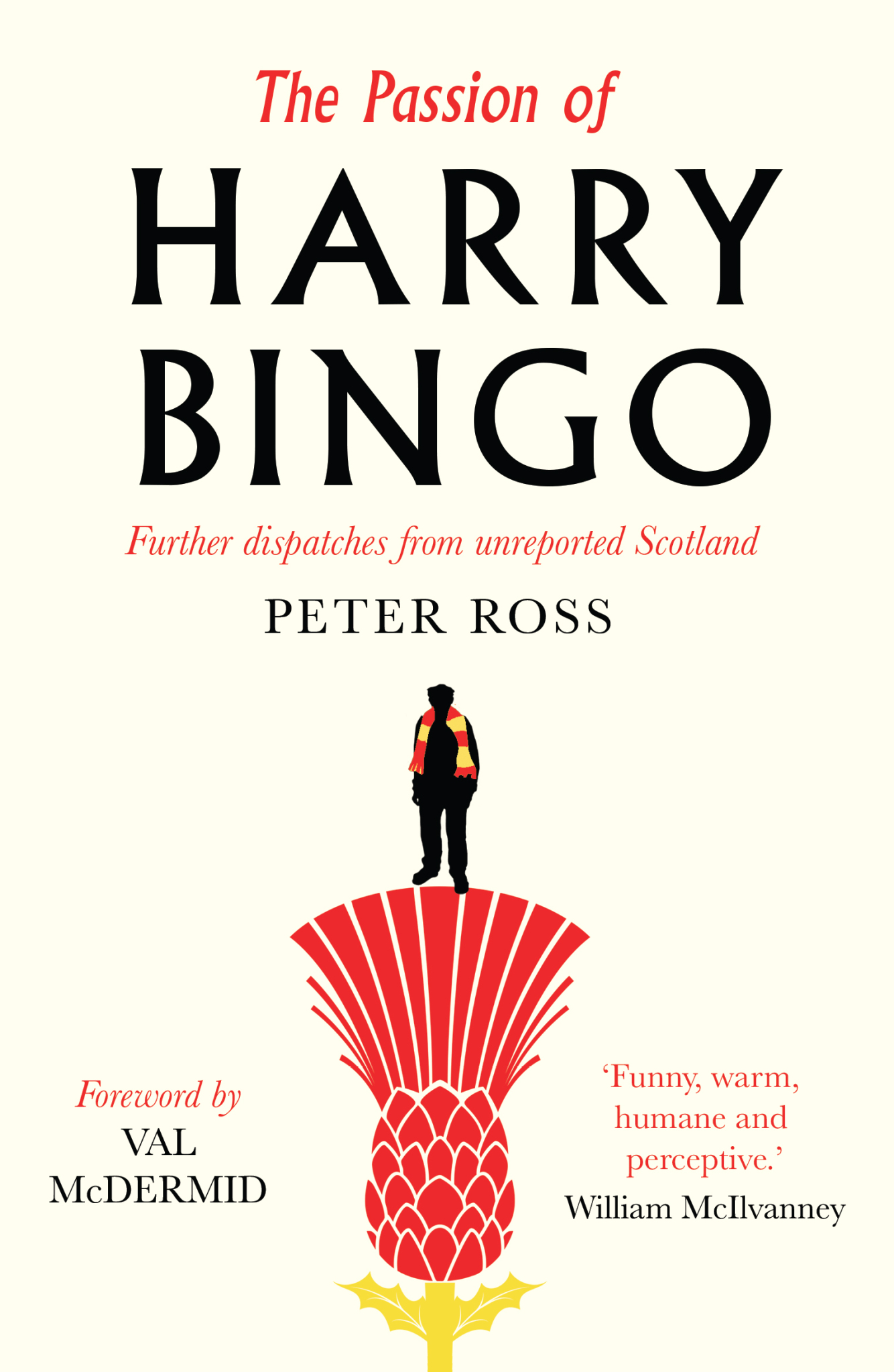

o celebrate the launch of his new book The Passion of Harry Bingo and our Piping Live tours, Peter Ross and his publisher Sandstone Press have graciously allowed us to use this wonderful piece by Peter on The Sikh Pipe Band’s appearance at Piping Live in 2015. Thanks also to Michael McGurk for allowing us to use his photograph. Keep an eye on our Facebook page later this week for a chance to win copies of The Passion of Harry Bingo. Over to Peter…

Beneath a Saltire blue sky, with Irn-Bru in their bellies and an old Punjabi war cry on their lips – ‘Sat Sri Akaal!’ – the men and women of the Sri Dasmesh pipe band march out into the grassy arena of Glasgow Green, the first time a Malaysian group has competed at the world championships, and give their medley laldy. ‘Gaun the Sikhs!’ shouts a turbaned fellow in the crowd.

The World Pipe Band Championships, known as ‘The Worlds’, is the Olympics of piping. Some 230 bands from sixteen nations, adding up to around 8,000 pipers and drummers, are taking part this year. The championships date back to 1906, but they have never seen anything quite like Sri Dasmesh.

Photograph by Michael McGurk

There are about forty of them, ranging in age from early teens to early sixties, tricked out in a manner that makes the uniforms of even their gaudiest rivals appear drab. Over white robes they wear a bright sash, a plaid in Royal Stewart tartan, and a faux tiger-skin apron, combining in one outfit the distinctive styles of Mason Boyne, Mary Doll Nesbitt and the Bay City Rollers. All of this, mind, topped with a turban and pink plume, or kalgi, bearing the symbol for ‘One God’. They look amazing: Glasgow fabulous; Kuala Lumpur dead brilliant.

That’s the city from which they have come, travelling 7,000 miles from the banks of the Klang to the banks of the Clyde. For many, this is their first time in the country from which the music they play originates. A homecoming of sorts.

‘This is an almost thirty-year dream coming true,’ says Sukdev Singh, the band’s founder, a tall, aquiline man with a silver beard and sovereign air. ‘When we set up the band, we would dream of one day just coming to Scotland. We had no idea there was such a thing as a world championship.’

Photograph by Peter Ross

His younger brother Harvinder, the fifty-two-year-old pipe major, takes up the story. ‘We were living in a world with no pipe bands. We didn’t even know what strathspeys or reels sounded like.’

Sri Dasmesh – named after the tenth guru of the Sikhs – was formed in 1986 by Sukdev, a commercial pilot. He had remembered, in childhood, hearing the skirl and drone coming from the police parade ground, back in the days (he considers them the good old days) of British rule. The sound and feeling stayed with him, and he decided, on graduation from university in the UK, to reintroduce bagpipe music to Malaysia. An instrument store was closing down, so he bought drums cheap, later adding Pakistani bagpipes which, Harvinder laughs, proved impossible to tune. Harvinder, in 1990, was dispatched to Glasgow for a week of lessons at the piping college, returning to Kuala Lumpur with the band’s first proper notation books, and a handful of CDs by some of the great bands. Here was treasure. The present generation of Sri Dasmesh – many of them the sons and daughters of original members – have grown up with this music from the cradle, and thus consider, say, the Shotts & Dykehead Caledonia Pipe Band to be hugely glamorous figures.

To visit Scotland and actually meet the likes of Jim Kilpatrick, Shotts & Dykehead’s drum major, has been overwhelming for the Malaysians. But they, too, have had their taste of fame. Everywhere they go on Glasgow Green, they are mobbed by members of the public wanting selfies. ‘Ah wis drawn tae them,’ says Jean Campbell, a sixty-one-year-old from Cumbernauld, enjoying a contemplative fag in the smoking area. ‘Thae turbans ur a magnet fur me.’

The last maharajah of the Sikh empire, Duleep Singh, sometimes known as the Black Prince of Perthshire, was deposed by the British in 1849 and exiled to Scotland, where he was petted and fêted by high society; Queen Victoria is said to have particularly admired his eyes and teeth. Yet even the Black Prince did not reach the benchmark of Scottish celebrity achieved by the Sri Dasmesh band – being interviewed for the lunchtime news by Jackie Bird.

During their fortnight in Scotland, the band have travelled around the country, competing at Highland games, and connecting with people of their faith past and present. Scotland is home to around 9,000 Sikhs. Sri Dasmesh have performed at gurdwaras – temples – in Glasgow and Edinburgh, and travelled to Kenmore, Perthshire, to pay their respects at the grave of Maharajah Duleep Singh’s infant son. They laid flowers and played ‘Highland Cathedral’; a moving and complex moment, a Sikh band from Malaysia playing Scottish music in a Christian kirkyard in tribute to the heir of a lost Indian kingdom.

There is something about the majesty of the music Sri Dasmesh plays that transcends the dark history from which it has emerged. ‘We should be a bit embarrassed by our colonial past, but if any good has come out of it, there it is,’ says Joe Noble, a Royal Scottish Pipe Band Association adjudicator and former world champion drummer, nodding towards the Sikhs. ‘The music was good and the music’s stayed. That’s our culture, and it’s brilliant that they are prepared to play it.’

Not just prepared, eager. Sri Dasmesh do not regard bagpipes as the instrument of the oppressor, but rather as an emblem of a shared history. ‘This is our mechanism for creating a bridge between our society, religion and community with the Scots,’ says Sukdev. More, they simply love the sound. Priya Kaur Kesh, an eighteen-year-old tenor drummer, was raised on Indian classical music, the daughter of a tabla player, and recalls the impact of hearing bagpipes for the first time six years ago: ‘I was shocked. Stunned. I had goosebumps. I thought, “I need to learn that asap.”’

On Saturday, after early prayers at the gurdwara on Berkeley Street, Sri Dasmesh travelled by coach to Glasgow Green for their heat. They were accompanied by their tutor Barry Gray, a no-nonsense middle-aged Australian who spotted the band in an Anzac Day parade three years ago and promptly ‘adopted’ them. Gray is a veteran musician well known for performing with whichever big rock and pop acts find themselves in Sydney and in need of a piper. He is no stranger to ‘Mull of Kintyre’. The good thing about working with a Sikh band, he says, is that they don’t get drunk. The bad thing is that their timekeeping is dreadful; he fines latecomers twenty pence a minute, and during one rehearsal in Kelvingrove Park raised twenty quid for the kitty.

Following their performance, the band wait anxiously for the results of the judging, damping down nerves with trays of chips ’n’ cheese, a Scottish delicacy for which they have developed a taste. The announcement, when it comes, is a triumph – they have qualified for the finals. They leap in the air, hug, tears rolling down cheeks; they get on their phones to home, breaking the news in excited Malay, Punjabi, English and Chinese. Later, their second performance will not go as well, but that doesn’t matter. Qualification was their goal and represents victory, as indeed does this whole journey.

I ask Tirath Singh, the eighteen-year-old pipe sergeant, how it feels, but he can hardly speak for crying. ‘This is my dream,’ he says, as the silver dagger at his waist glitters in the Scottish sun.

Also available by Peter Ross: Daunderlust